6 November 2022 Bulletin

Click to read this weekend’s bulletin: 6 November 2022 Bulletin

Click to read this weekend’s bulletin: 6 November 2022 Bulletin

Click to read this weekend’s bulletin: 30 October 2022 Bulletin

O most sweet Jesus, through the bloody sweat which Thou didst suf- fer in the Garden of Gethsemane, have mercy on these Blessed Souls. Have mercy on them.

R. Have mercy on them, O Lord.

O most sweet Jesus, through the pains which Thou didst suffer during Thy most cruel scourging, have mercy on them.

R. Have mercy on them, O Lord.

O most sweet Jesus, through the pains which Thou didst suffer in Thy most painful crowning with thorns, have mercy on them. R. Have mercy on them, O Lord.

O most sweet Jesus, through the pains which Thou didst suffer in car- rying Thy cross to Calvary, have mercy on them.

R. Have mercy on them, O Lord.

O most sweet Jesus, through the pains which Thou didst suffer during Thy most cruel Crucifixion, have mercy on them.

R. Have mercy on them, O Lord.

O most sweet Jesus, through the pains which Thou didst suffer in Thy most bitter agony on the Cross, have mercy on them.

R. Have mercy on them, O Lord.

O most sweet Jesus, through the immense pain which Thou didst suf- fer in breathing forth Thy Blessed Soul, have mercy on them.

R. Have mercy on them, O Lord.

(Recommend yourself to the Souls in Purgatory and mention your intentions here).

Blessed Souls, I have prayed for thee; I entreat thee, who are so dear to God, and who are secure of never losing Him, to pray for me a miserable sinner, who s in danger of being damned, and of losing

God forever. Amen.

We must empty Purgatory with our prayers. St.Padre Pio

Click to read this weekend’s bulletin: 23 October 2022 Bulletin

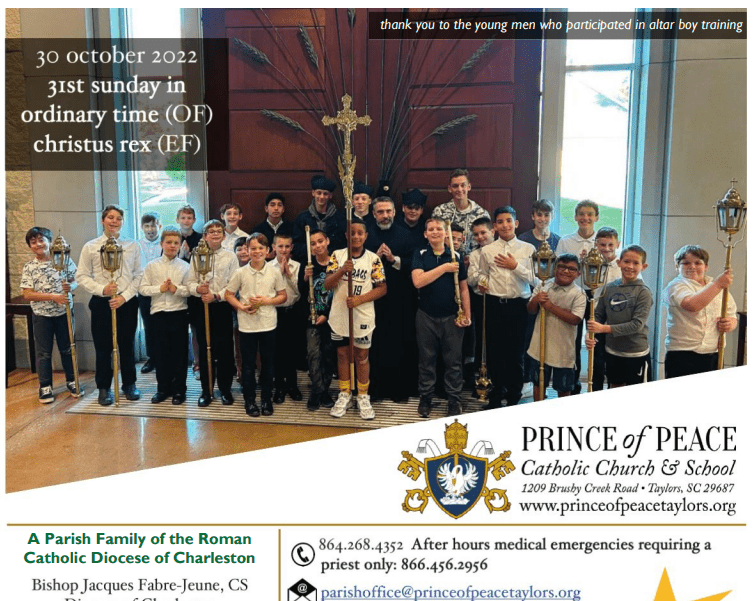

Click to read the Annual Financial Report for the period ending 30 June 2022

Dear Friends in Christ,

The past two end of year financial reports for Prince of Peace Catholic Church and School were very strange ones to write indeed, because of how COVID affected operations over those two fiscal years. While many Catholic parishes throughout the world saw a collapse or tremendous difficulty with numbers, Prince of Peace was truly a miracle story. Forward thinking leadership and flexibility during a constantly changing situation, as well as the determination of our parishioners to keep their parish going, meant that we actually emerged from the crucible of the pandemic in a stronger situation than we were before it. It was both edifying and amazing to me how people found their way to this parish and school community during that time.

What is even more interesting is how many people stayed. Our school enrollment, as you will see, had a significant uptick during the pandemic because we were in a situation to offer an educational experience other schools could not provide during that time. I was convinced that many of those families would leave after the pandemic, but they didn’t. The value of a POPCS education was apparent to them, and they chose to stay, as well as recruit others for the school community.

The way we navigated the constantly changing requirements of public and ecclesiastical authorities while trying to respect widely divergent expectations and opinions on how to do things at church ended up actually attracting a large number of families from all over the country to the parish. During that time, we didn’t drop anyone from the rolls. We finally began to do a proper assessment of our membership, especially after a number of deaths of some very beloved and active parishioners. The result of that evaluation is a slight decrease in the number of registered active households, but the actual number of average bodies in the pews went up considerably, as well as new families joining the parish.

This past year saw an incredible output of capital improvements to the facilities on campus, and even the inauguration of the Great Nativity. This year as we start our Advent Market, we have an opportunity to bring Prince of Peace more into the wider community. Winning the Best Place of Worship in the Upstate award from the Greenville News in a Baptist town like Greenville is one of the most miraculous things to happen to us in the history of the parish. It is a testament to the fact that you really believe in what we do

here, and want to see it successful. And you are putting your money where your mouth is, and that investment is allowing us to do some incredible things.

I want to thank you for your generosity, and encourage you to keep that spirit of giving alive in the upcoming fiscal year. As financial forecasts for our country predict some tight times ahead, we will adjust along with you, but the more we band together and have everyone do their part, the more we can do so much for the love of God and others!

Yours in the Prince of Peace,

Fr Christopher Smith, STD

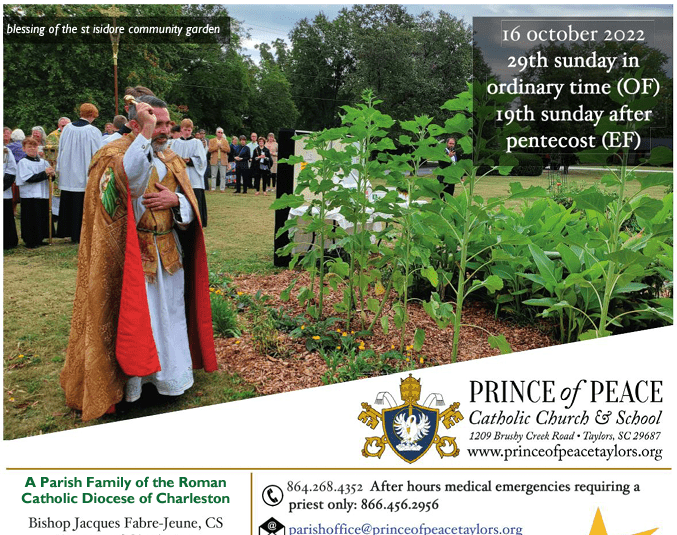

Click to read this weekend’s bulletin: 16 October 2022 Bulletin

Congratulations to the Charity Golf Tournament organizers, under the direction of Brian Mackenzie, who raised $46,400 with the support of generous sponsors and players to benefit both St Rafka Maronite Catholic Church & Prince of Peace Catholic Church. Each parish receives $23,200 for their capital projects. For our parish, this funding supports critical campus security updates!

![]() The BMW Performance Center Team won with a net score of 41 (31 under par). The players on that team were Chad Hendley, Todd Achberger, Keith Alf, and Derek Brown.

The BMW Performance Center Team won with a net score of 41 (31 under par). The players on that team were Chad Hendley, Todd Achberger, Keith Alf, and Derek Brown.

![]() The second place team had a net score of 44 (28 under par). The players on this team were Logan Pendergrass, Adam Moore, Lee Coleman, and Keith Willis.

The second place team had a net score of 44 (28 under par). The players on this team were Logan Pendergrass, Adam Moore, Lee Coleman, and Keith Willis.

![]() The third place team had a net score of 45 (27 under par). The players on this team were Will Morrow, Bill Francis, Bill Fayssoux, and Michael Spiers.

The third place team had a net score of 45 (27 under par). The players on this team were Will Morrow, Bill Francis, Bill Fayssoux, and Michael Spiers.

![]() The event had two hole-in-one golfers – both at hole #15!

The event had two hole-in-one golfers – both at hole #15!

Thank you to our incredible sponsors:

Blue Ridge Electric

BMW

Bob & Jacque Dumit

Bouharoun Package

Brian & Pam Mackenzie

Brown & Brown Insurance

Charles Howard

Cherokee Valley Club

Clayton Construction

Cobbs Glen Golf

Coca Cola

Corley Plumbing Air Electric

Dan Sundahl/Ellen Donohoe

Dick’s Sporting Goods

Erna Liebrandt

Felicia Griggs Realtor

Francis Produce

Golf Galaxy

Goosehead Insurance

Greenville Spine

Interstate Landfill

J Francis Builders

Legacy Pines Golf

Links O’Tryon Golf

Miller Law Firm

Palmetto State Transportation

Pepsi

Pickens Golf Club

Preferred Home Services

Priority One Security

ProVista Advisors

Rich Haddad Insurance Agency

Rockland Trust

Saad and Manios LLC

Saluda Valley Country Club

Smith & James

SC Premier Signs

Smithfields Country Club

Squandroni, Bill

South State Bank

Southern Oaks Golf

Spinx

Thomas McAfee Funeral Homes

Toyota of Easley

Trattoria Giorgio

Two Chefs

Universal Packaging

William Francis

Willow Creek Golf

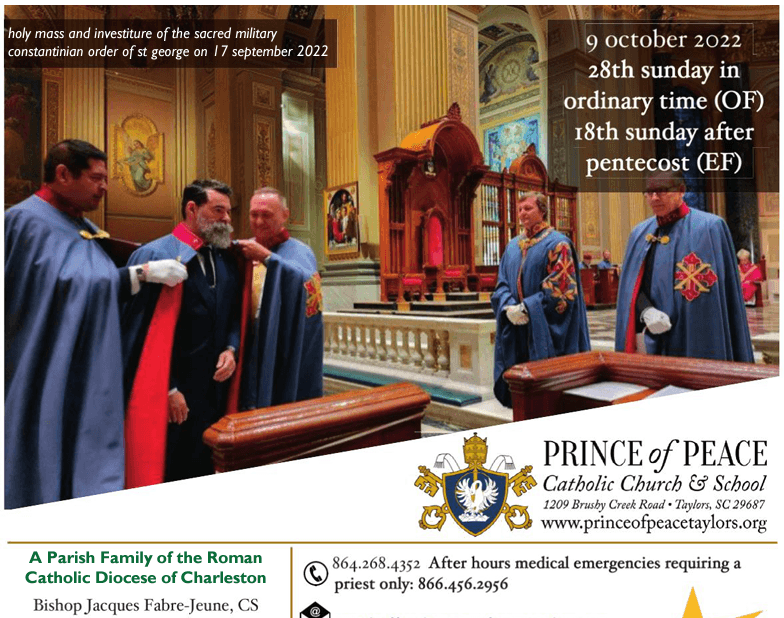

Click to read this week’s bulletin: 9 October 2022 Bulletin

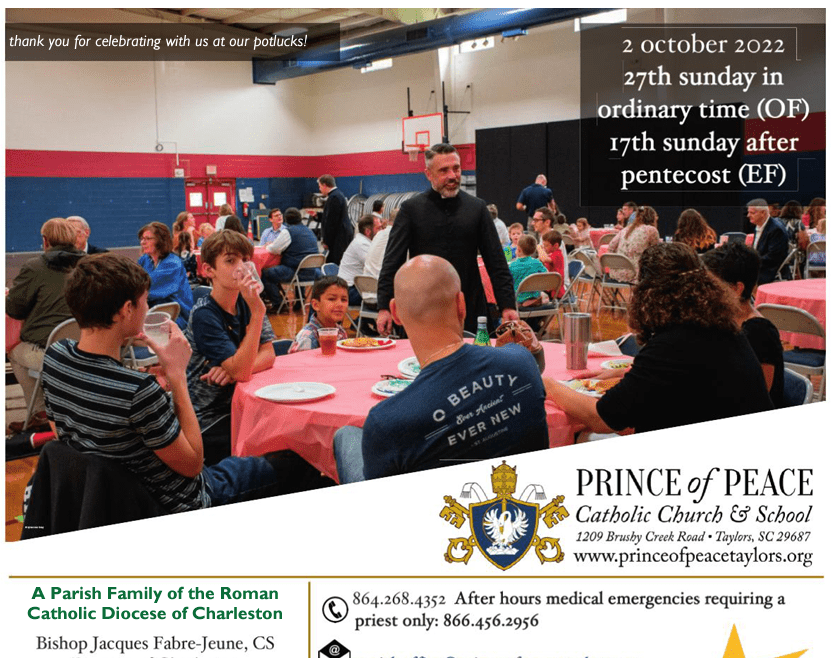

Click to read this weekend’s bulletin: 2 October 2022 Bulletin

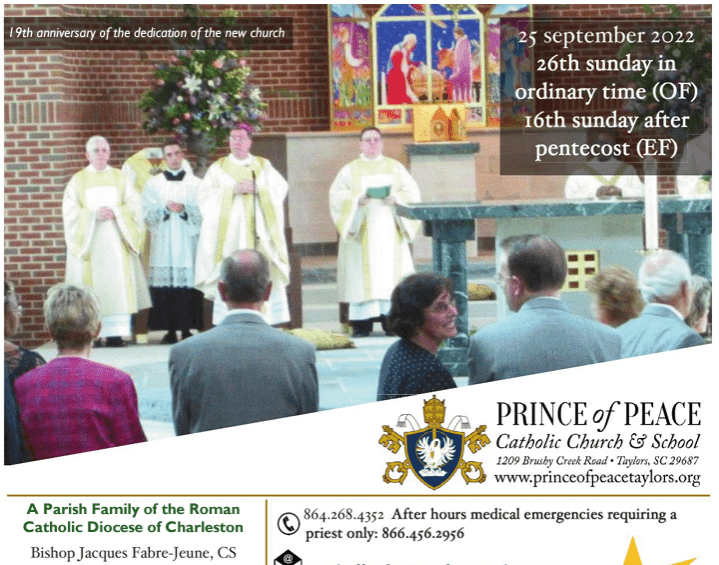

Click to read this weekend’s bulletin: 25 September 2022 Bulletin

Recent Comments