Explanation of the Vesting Prayers Before Mass

Please watch our show and tell instruction about what the priest does to prepare to celebrate Holy Mass, so that we may offer our prayers in union with him as he ascends Calvary to re-present the Sacrifice in the person of Christ the Head. We offer this catechesis as a way to understand better what we experience at Mass.

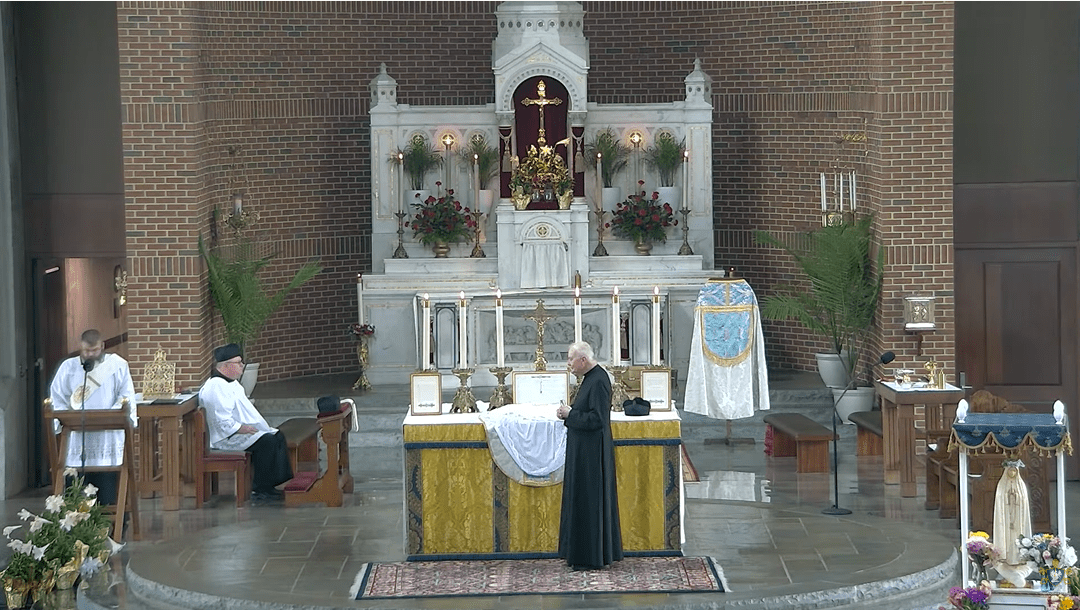

The Altar

The central focus of the liturgical action of the Mass is the altar of sacrifice where the sacrifice of redemption is renewed. Here, the bloody total self-gift of Jesus to His Father in the unity of the Holy Spirit on Golgotha is made present to us in an unbloody manner under the sacramental veils of bread and wine, as we share the fruits of that one sacrifice in Holy Communion. Ordinarily, the altar is made of stone, and has five crosses engraved into it, which represent the fie wounds of Our Lord on the Cross. Towards the front of the altar, or in the pedestal of the altar, are buried the relics of saints and martyrs who gave their lives for Christ. In our altar, we have the relics of Ss. Linus and Callistus, two of the successors of St Peter as Pope, as well as St Pius X and St Elizabeth Ann Seton, our first American saints. On top of the altar are three cloths, which recall the cloths in which Our Lord was swathed in the manger in Bethlehem, the binding cloths which held Him in the tomb and the cloth that was placed over His Holy Face in that sepulchre. The stone slab of the altar represents the anointing stone and the altar itself the tomb. Before an altar is set apart for divine worship, the Bishop anoints it with sacred chrism and burns incense upon it to remind us that here we worship Christ – the Anointed One – and that our prayers rise to heaven as sweet perfume before the Lord, in union with the prayers of all the saints and angels in heaven who constantly minister at the throne of Grace.

Also on top of the altar is found at its center an image of the Crucified Lord, to remind us that at Mass we stand at Calvary. Six candles surround the Cross, all images of the light that comes from the Resurrection so that the altar is ablaze with the light of glory. On solemnities and feasts, the altar may be further adorned with flowers or with the relics of the saints to add to the Church a greater sense of joy. The candles are ordinarily of beeswax, and are unbleached during the penitential seasons of Advent and Lent, and bleached particularly when the Blessed Sacrament is exposed for adoration.

The Priest prepares for Mass

Whenever the priest goes to celebrate Mass, he prepares for prayer – with prayer. He places himself in the presence of Almighty God, and calls to mind the specific intention for which he is going to celebrate Mass. Although they are optional now, it was common for the priest to pray a number of psalms and prayers to remind him of the sacredness of this action and how unworthy he is to minister at the altar. When he is ready, he enters the sacristy, the room of preparations for sacred worship. He washes his hands, and prays, Give strength to my hands, Lord, to wipe away all stain, so that I may be able to serve Thee in purity of mind and body. The priest of the New Covenant is the inheritor of the fulfillment of the sacrifices of the Old Law, and so he washes his hands before offering the sacrifice just as the Jewish priests and levites performed purification rituals with water before this work offered on behalf of the people, which is what the Greek word liturgy means.

The priest is now in his black cassock, that ankle-length garment whose black color symbolizes death to the world. The cassock ordinarily has thirty three buttons down the front, one for each of the years Our Lord spent on earth, and five buttons on the sleeves, for each of the five wounds of Christ on the Cross. The cassock is a reminder that the priest must put sin to death so that Christ can live through him. It can be replaced by white in tropical climates, and is purple for bishops, the ancient sign of royal leadership, and scarlet for cardinals, for the call to martyrdom and the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

The priest then puts on each of the sacred vestments the Church prescribes for her sacred ministers when they celebrate Holy Mass. These vestments are the continuation of both Jewish and pagan ceremonial dress, to underscore the continuity of Catholic worship with the liturgy of ancient Israel and the virtue of natural religion. The inner vestments are ordinarily of linen, but also now are often made in cotton or various blends. They are white, to symbolize the purity of the baptized soul in Christ. Over them, are the outer vestments specific to the day, and are ordinarily of silk or some other precious material, as is befitting the dignity of our royal service to the King of Kings. These vestments come in colors which have been associated since ancient times with various aspects of Christian life. Green during the ordinary time after Epiphany and Pentecost indicates growth, just as so many living things in the world are green. Red is for the blood of martyrdom and the fire of the Holy Spirit come down upon the Apostles at Pentecost. Purple is the ancient sign of both royalty but also of penance, as it is close to black, the color of mourning. At the midway points of Advent and Lent, purple is muted to joyful rose in expectation of the coming feasts of Christmas and Easter. White is the color of feasting and purity, for the greatest solemnities and memorials of the saints, and can be replaced by cloth of gold or silver.

The first inner vestment the priest puts on is the amice. He kisses the cross on it as a sign of reverence and places it momentarily over his head before resting it on the shoulders to protect the other vestments from his own sweat! It is fastened around him with white or red ribbons, and comes from the Latin word, amictus, which means to wrap around. As he dons the vestment, he prays that he may be protected from the assaults of the Evil One, whose dominion was destroyed by the reality the Mass commemorates. He prays, Lord, set the helmet of salvation upon my head, to fend off all the assaults of the devil.

Over the amice he places the alb, which comes from the Latin alba, meaning white. It calls to mind the white garment with which we are clothed in baptism, where we are covered by Christ: though your sins may be as scarlet they are now as white as snow. The alb comes from the Roman toga, the garment proper to scholars. It is appropriate for the priest to wear this garment, as he is enlightened by sacred truth and commanded to teach it. The priest prays, Make me white, O Lord and cleanse my heart, that being made white with the Blood of the Lamb, I may deserve an eternal reward.

The priest than gathers the vestments together with a braided cord of linen called the cincture, which is wrapped tightly around the priest’s waist to remind him of the virtue of chastity. Gird me O Lord with the cincture of purity, and quench in my heart the fire of concupiscence, that the virtue of continence and chastity may abide in me. The cincture can be white or colored.

The priest then places on his left wrist the maniple, the first of the outer vestments the color of the day. The word manipulum in Latin means a sheaf of grain, or something carried in a small bundle. It is the remnant of a larger more ancient vestment that included a handkerchief to wipe away sweat and tears from the priest’s face at Mass. He prays, May I deserve, O Lord, to bear the maniple of weeping and sorrow in order that I may joyfully reap the rewards of my labors. It is a reminder that Christian life in this valley of tears is not our true home, and can be a place of suffering, where the priest in the person of Christ must work hard to show souls beyond the Cross to the Resurrection.

The next outer vestment is the stole, which comes from a Roman symbol of authority. The stole is the symbol of the fact that the priest receives authority from the Church to celebrate the sacraments, and is, in fact, worn in the celebration of all of the sacraments. Traditionally, a priest would wear his stole crossed in front, and a bishop would wear his stole straight down, as a sign that only the bishop has the fullness of the priesthood, and that the ministry of the priest is limited by his obedience to the bishop. Roman judges used the stole as a sign of the authority, but the Church employs it as a sign that the True Law is that of Grace and lived in obedience to the Word of God. The priest kisses the cross embroidered on it, and prays, Lord, restore the stole of immortality, which I lost through the collusion of our first parents, and as unworthy as I am to approach these sacred mysteries, may I yet gain eternal joy.

The priest immediately then puts on the largest and most conspicuous of the vestments: the chasuble. The Latin word casula means “little house”, and is like a shelter thay covers the priest. The chasuble covers up the stole, and symbolized charity, which must cover all things, even authority. O Lord, who has said, My yoke is easy and My burden light, grant that I may so carry it as to merit Thy grace.

The priest then covers his head with the biretta, the scholars’ cap of old, which from its soft form has now hardened into three peaks symbolizing the Most Holy Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit, in whose Name the Mass is true and perfect worship. When the People of God have been gathered in the church for Mass, and the acceptable time has drawn near, we leave behind chronos, the changing time of this world, and enter into Kairos, the timeless expanse of eternity whose veil is drawn back just a little bit at every Holy Mass. He bows to the Cross in the sacristy, and the server rings the bell, the joyful signal to the faith to rise and greet the Lord who comes in their midst to renew the Paschal Mystery in the heart of the Church. Mass has finally once again begun.

Recent Comments