22 August 2021 Bulletin

Click to read this week’s bulletin: 22 August 2021

Click to read this week’s bulletin: 22 August 2021

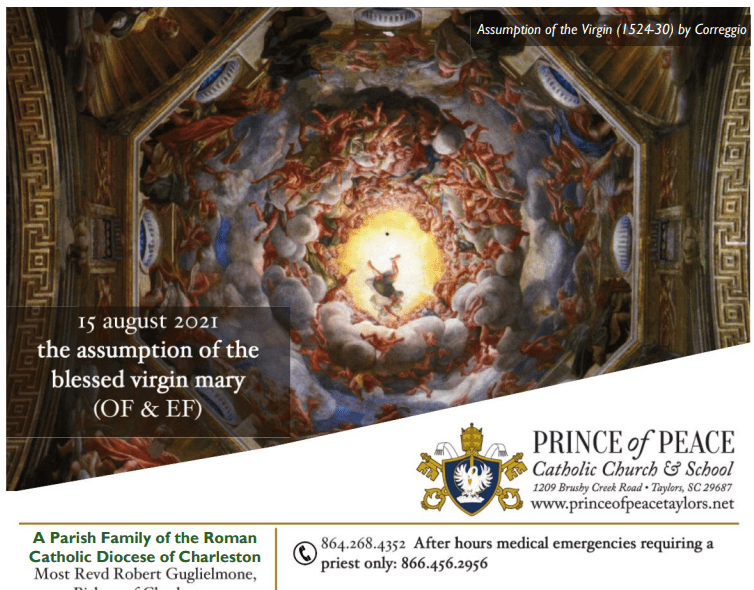

Click to read this week’s bulletin: 15 August 2021

Click to read the 8 August 2021 Bulletin!

20 August: Feast of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. Born in 1090, Bernard spent his early years near Dijon, France. His family was of Burgundian landowning aristocracy; he had five brothers and one sister. Bernard’s parents were exceptional models of virtue. It is said that his mother exerted a virtuous influence upon Bernard only second to what St. Monica had done for St. Augustine. Her death in 1107 so affected Bernard that he claimed that it was when his “long path to complete conversion” began. He turned away from his literary education toward a life of denial and solitude. He joined the Cistercians at age 22. Bernard was so passionate about his faith that he convinced his brothers, his uncle, and many of his friends to join him at the abbey. Bernard first entered the abbey at Citeaux, but only three years later was sent with 12 other monks to establish another monastery in the Diocese of Champagne. The monastery came to be known as Clairvaux (Valley of Light). He led the other monks there as the abbot for the rest of his life. Bernard’s physical ailments during this time may account for consistent partiality for physical rigors. He was plagued most of his life by impaired health (anemia, migraines, gastritis, hypertension, an atrophied sense of taste). However, as Bernard’s health worsened, his spirituality deepened. He also learned how to combine the contemplative life with important missionary work. Bernard was known for his strict observance of silence and contemplation; but these practices did not impede him from living a very intense apostolic life. Bernard taught the faith with humility. He was known for his focus on the truth that God, who is love, created mankind out of love and that man’s salvation consists of adhering firmly to Divine love, revealed through the crucified and risen Christ. Saint Bernard is also well-known for his Marian devotion, especially in using and promoting the “Memorare” prayer. Pope Pius VIII labeled Bernard as the “Honey-Sweet Doctor” for his eloquence in sharing the faith. Bernard continued to write and give sermons and he traveled throughout Europe defending the Christian faith. As the confidant of five popes and a major figure in church councils, Bernard considered it his role to assist in healing church wounds inflicted by the antipopes and to oppose rationalistic influences of the time. His greatest literary work is titled “Sermons on the Canticle of Canticles.” In it, St. Bernard wrote: “The Father is never fully known if He is not loved perfectly.” And, “Whence arises the love of God? From God. And what is the measure of this love? To love without measure.” St. Bernard was declared a doctor of the church in 1830, thanks to his many writings and sermons which greatly influenced Europe in the 12th century and his efforts which helped to avoid a schism in the Church in 1130. Bernard was extolled in 1953 as doctor mellifluus in an encyclical of Pope Pius XII; he was canonized in the year 1174. Saint Bernard is the patron of beekeepers; candlemakers; wax refiners; Gibraltar; Queens College, and Cambridge.

“What we love we shall grow to resemble.” – St. Bernard of Clairvaux

Ideas for celebrating this feast at home:

(sources: catholicculture.org; catholicnewsagency.com; britannica.com)

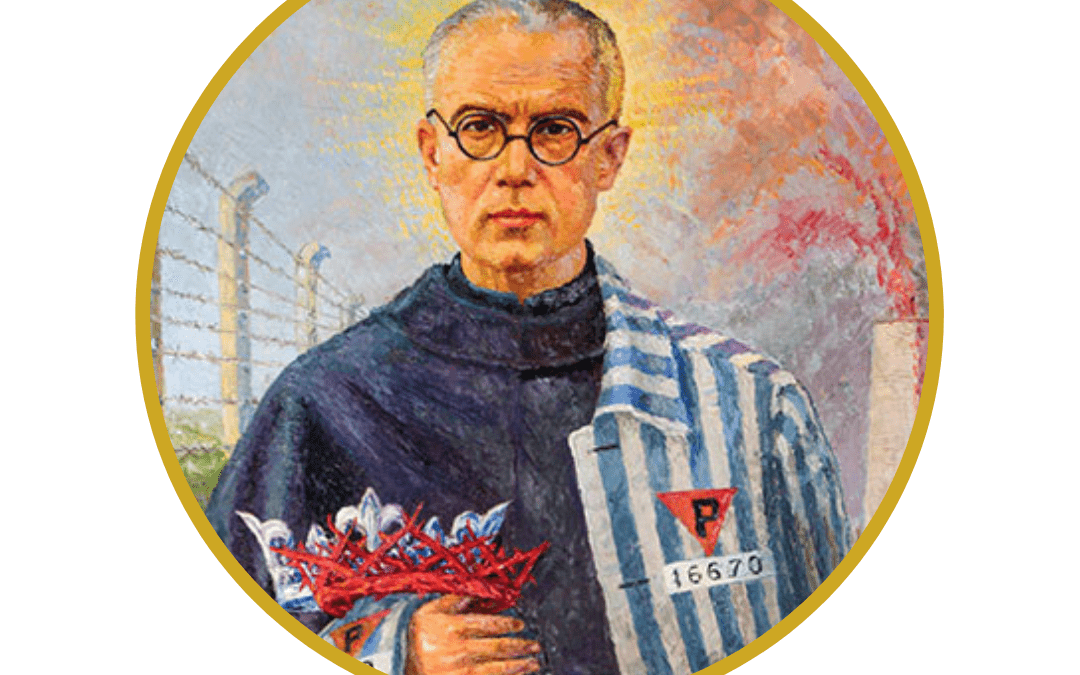

Saint Maximilian was born Raymond Kolbe in Poland in 1894. As a youth, he had a vision from the Blessed Mother. He described it best himself: “That night, I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.” In 1910, he entered the novitiate of Conventual Franciscan Order and was given the name Maximilian. He was sent to study in Rome where he was ordained a priest in 1918. After returning to Poland in 1920, he wrote: “I must be a saint, the greatest saint possible. Remember that you are the absolute, unconditional, unlimited, irrevocable property of the Immaculate… My life, my death and my eternity are yours, O Immaculate. Do with me whatever you wish.” Back in Poland, Father Maximilian organized his Militia of the Immaculate Virgin Mary – a movement of Marian consecration. In 1922, he published the magazine, “Knight of the Immaculate” to promote devotion to Mary. In 1927, he built a town called the “Town of the Immaculate,” outside of Warsaw. There he trained ‘apostles of Mary’. By 1939, the City had expanded from 18 friars to 650, making it the world’s largest Catholic religious house. To better “win the world for the Immaculata,” the friars utilized modern printing techniques. They published countless catechetical and devotional tracts, a daily newspaper and a monthly magazine with a circulation of over one million. Maximilian started a shortwave radio station –he was a true “apostle of the mass media.” He was also a ground-breaking theologian. His insights into the Immaculate Conception developed understanding of Mary as “Mediatrix” of all graces and as “Advocate” for God’s people. In 1941, the Nazis imprisoned Father Maximilian in Auschwitz. In July, it was reported to the camp commander that a prisoner had escaped. In order to set an example, they selected ten men for the starvation bunker. When a man near him was chosen, a man who cried in protest because he had a family, Maximilian bravely stepped forward and said “Let me take the place of this man. I am a Catholic priest.” Maximilian was taken to endure an excruciatingly slow death. On August 14, 1941, the vigil of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Father Maximilian’s two-week ordeal in the starvation bunker was brought to an end by an injection of carbolic acid. Of the ten victims, he was the last to die. “Hail Mary!” was the last prayer on the lips of Father Maximilian, as he offered his arm to the person injecting the acid. In 1982, Saint JP II canonized Maximilian Kolbe as a “martyr of charity.” Saint Maximilian Kolbe is considered a patron of journalists, families, prisoners, the pro-life movement and the chemically addicted.

“Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:12)

Ideas for celebrating this feast at home:

(sources: catholicculture.org; saintmaxmiliankolbe.com; showerofrosesblog.com)

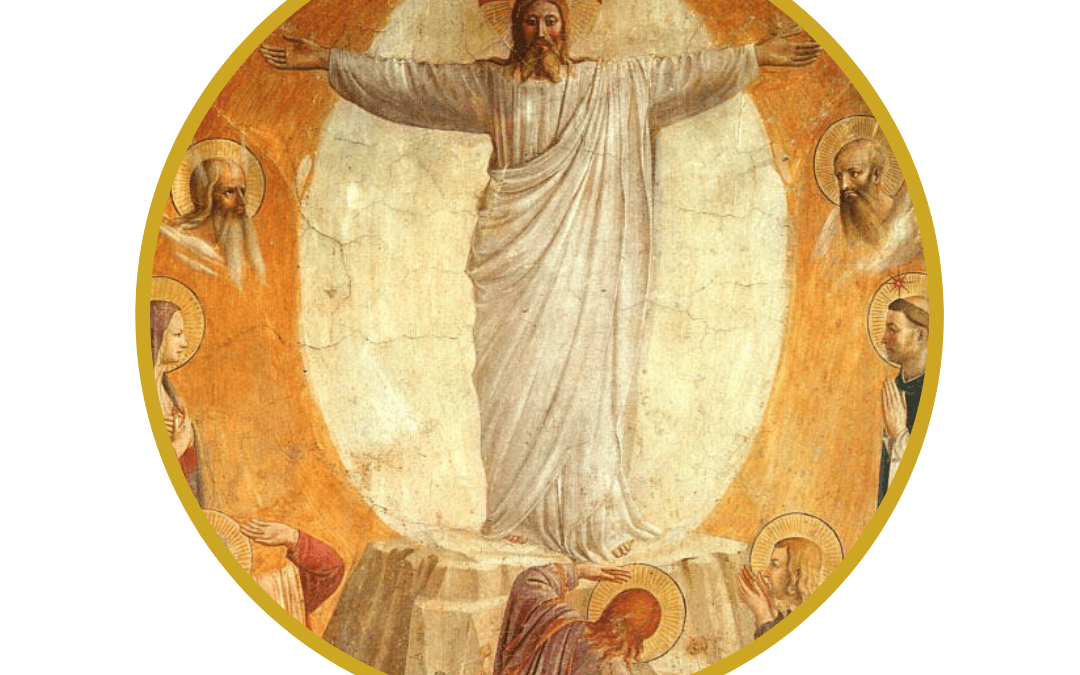

6 August: Feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord. The Transfiguration is one of the major events in the earthly life of Jesus. The gospels tell the story of Jesus bringing Saint Peter and the two sons of Zebedee, Sts. James and John, up to the top of a high mountain to pray (tradition holds that it was Mount Tabor). This would have been about a year before Our Lord’s passion. While he was praying, Jesus’ appearance changed and his clothing became dazzling white: “His face shone like the sun, and his garments became white as light” (Mt 17:2). Next, Moses and Elijah appeared in glory and spoke with Jesus of things that were to come. The disciples were amazed and overwhelmed. Unsure what to do, St. Peter offered to put up tents for Jesus and his friends. Although they had been with Jesus for three years, the disciples still did not really understand who He was. Then, a cloud overshadowed them. They became frightened and heard a voice from Heaven saying: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.” (Mt 17:5). After Moses and Elijah disappeared, Jesus instructed the disciples not to tell anyone about this “until the Son of man has been raised from the dead” (Mt 17:9). This event, called the Transfiguration, is significant in the Christian faith. Saint Thomas Aquinas called it “the greatest miracle” because it revealed the divinity of Christ before his passion and death. In the Transfiguration, Christ enjoyed for a short while that glorified state which was to be permanently His after the Resurrection. The splendor of His inward Divinity and of the Beatific Vision of His soul overflowed on His body, and permeated His garments so that Christ stood before Peter, James, and John in a snow-white brightness. This feast day became widespread in the West in the 11th century and was introduced into the Roman calendar in 1457 to commemorate the victory over Islam in Belgrade. Before that, the Transfiguration of the Lord was celebrated in the Syrian, Byzantine, and Coptic rites. The Transfiguration foretells the glory of the Lord as God, and His Ascension into heaven. It anticipates the glory of heaven, where we shall see God face to face, in all of His dazzling glory.

Ideas for celebrating this feast day at home:

Recent Comments